Image Credit: @thespongs / YouTube

Origins & The DPZ Vision

Cornell's story begins in the late 1980s when the Province of Ontario found itself owning 500 acres of underused land originally expropriated for a planned airport. Rather than pursuing conventional suburban development, the Province partnered with the Town of Markham to create something different.

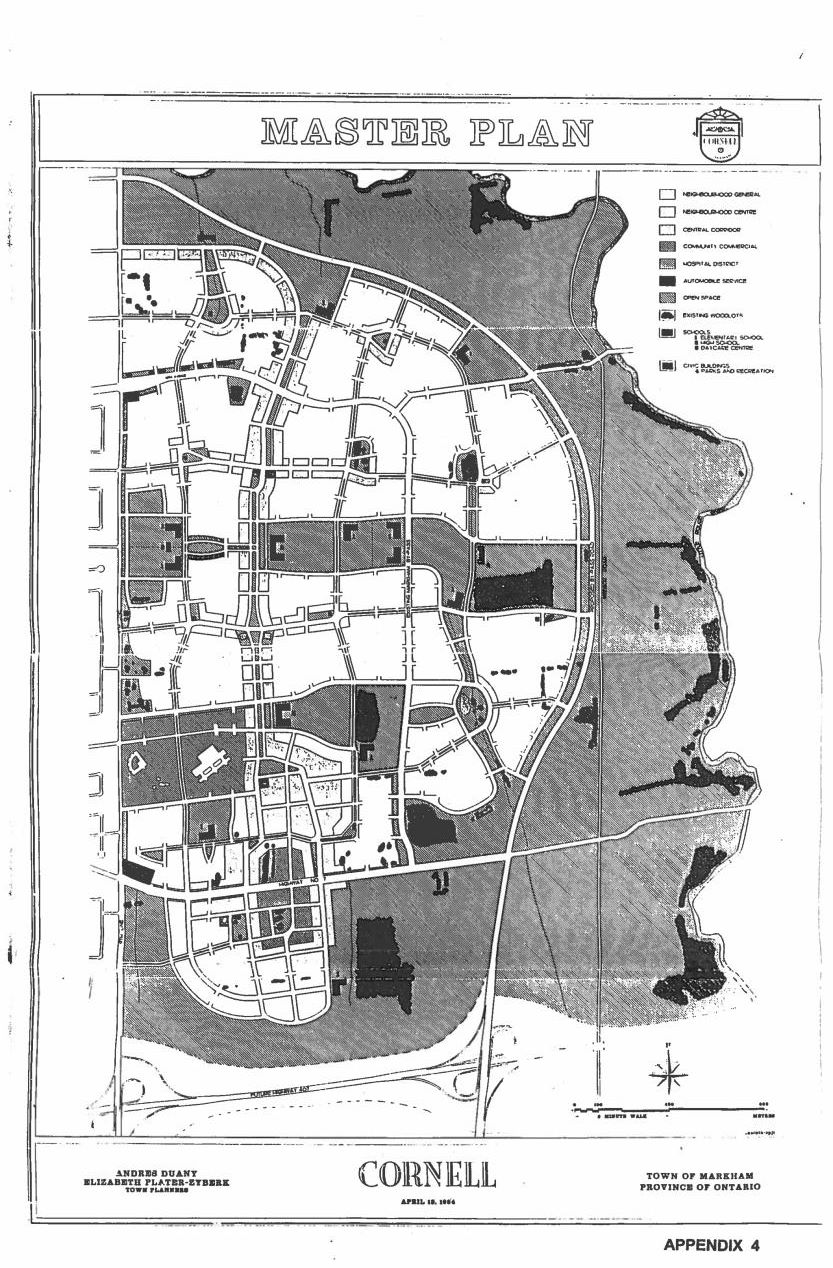

Cornell Master Plan created by Duany Plater-Zyberk and Associates (1994) [Source: Victoria Moore]

The International Design Competition

In 1992, after sending out a request for proposals, the Province held an international design competition. Duany Plater-Zyberk and Associates (DPZ) of Miami—the firm that would become synonymous with New Urbanism—won the competition and were hired to design the vision for Cornell.

The Charrette Process

DPZ led a groundbreaking five-day design charrette in April 1992, involving planners, engineers, developers, residents, and city officials. This participatory process helped build consensus around innovative plans that differed dramatically from conventional suburban development.

The charrette was exceptionally successful, with over 1,000 citizens attending the final presentation. Markham residents and politicians, who lived in lower-density single-use subdivisions, began to accept higher-density, mixed-use neighbourhoods as a planning objective.

Key Design Principles

- Traditional Neighbourhood Design: Grid street patterns with rear laneways instead of front driveways

- Housing Diversity: Mix of single-family, semi-detached, townhouses, and secondary suites

- Walkability: Five-minute walk neighbourhoods with amenities within walking distance

- Mixed-Use Integration: Commercial and residential uses combined in town centers

- Environmental Sensitivity: Preservation of natural features and creation of green corridors

Housing Innovation & Diversity

Cornell pioneered several housing innovations that were rare in Canada at the time, creating a model for diverse, affordable housing within a single neighbourhood.

Semi-detached homes showing the variety of housing types side-by-side [Source: Victoria Moore]

Revolutionary Zoning Changes

Cornell essentially rewrote Markham's zoning to permit a mix of housing options side-by-side. Each residential block was required to feature at least two building types, creating visual interest and housing options for different income levels and life stages.

Coach Houses

Cornell was the only subdivision in Markham to provide laneway housing as an affordable rental option. These small, independent dwelling units above detached garages created rental opportunities while providing homeowners with mortgage helpers.

Coach house above detached garage accessed from rear laneway [Source: Victoria Moore]

Contemporary with East Clayton

Cornell's development paralleled another pioneering New Urbanist project in British Columbia: East Clayton in Surrey, which, like Cornell, relies on coach houses to accomodate more diverse housing needs. While East Clayton focused on sustainable infrastructure and environmental design under the leadership of UBC's Patrick Condon, Cornell represented the full DPZ New Urbanist vision transplanted to Canada. Both projects, developed in the 1990s and early 2000s, served as crucial tests of whether New Urbanist principles could work in Canadian suburban contexts, providing valuable lessons for municipalities across the country.

Secondary Suites & Live-Work Units

Most single-family homes were designed to include legal secondary suites, effectively doubling housing capacity. Live-work units allowed ground-floor commercial spaces within residential areas, supporting small businesses.

Housing Types in Cornell

- 36% single-detached units

- 46% townhouses

- 17% semi-detached homes

- 1% apartment-style housing

- Gross density: 19.6 units per hectare (vs. 11.6 for conventional suburbs)

This variety allows families to remain in the same community as their needs change, from first-time buyers to growing families to empty nesters and seniors.

Street Design & The Laneway Model

One of Cornell's most distinctive features is its comprehensive laneway system, which separates vehicular access from pedestrian streetscapes. This design draws from 19th-century precedents but required significant adaptation for Canadian conditions.

Adapting to Canadian Climate

Unlike New Urbanist communities in the southern United States, Cornell had to solve the challenge of snow removal. Early laneways were built 8.5 to 9.5 meters wide to accommodate snow plows and storage, with corner lots providing unpaved easements for snow disposal.

Benefits of the Laneway System

- Pedestrian-Friendly Streets: Front yards and porches face walkable streets without garage doors dominating

- Hidden Parking: Cars and garbage collection moved to rear lanes

- Emergency Access: Police and fire departments praised dual access to properties

- Housing Opportunities: Space for coach houses and secondary suites

- Community Spaces: Laneways become informal gathering places for neighbors

Neighbourhood showing housing density with three-story homes and coach houses in laneways [Source: @thespongs / YouTube]

Grid Street Pattern

Cornell's street network follows a traditional grid pattern with short blocks, creating high connectivity and multiple route options. This contrasts sharply with the cul-de-sac and curvilinear streets of surrounding conventional suburbs.

Cornell laneway showing how these spaces become streets of their own with coach houses [Source: @thespongs / YouTube]

Street Design Features

- Sidewalks on Both Sides: Mandatory throughout Cornell, unusual for suburban areas at the time

- Tree-Lined Streets: Extensive landscaping and medians for traffic calming

- On-Street Parking: Parallel parking provides buffer between pedestrians and traffic

- Reduced Setbacks: Homes closer to sidewalks with prominent front porches

- Five-Minute Walk Scale: Neighbourhoods designed so key destinations are within a quarter-mile

Implementation Challenges

Markham's Public Works Department initially opposed the laneway model due to snow removal concerns and costs. However, collaboration between planners, consultants, and public works staff led to innovative solutions that made the system work.

Mixed-Use: Zoning Flexibility vs. Market Reality

Cornell's approach to mixed-use was groundbreaking for its flexibility, allowing commercial and residential uses to be integrated throughout the community rather than segregated into separate zones. This zoning innovation enabled everything from live-work units to corner stores to emerge organically within residential neighbourhoods.

Fine-grained mixed-use at the corner of Bur Oak Ave and Morning Dove Drive, showing how Cornell's flexible zoning allowed commercial uses to integrate into residential areas [Source: Loozrboy, Wikimedia Commons]

Two Models, Different Outcomes

Cornell's mixed-use development followed two distinct approaches with notably different results:

Neighbourhood-Integrated Mixed-Use

The more successful approach integrated small-scale commercial uses directly into residential blocks. Corner stores, live-work units, and small offices were woven into the neighbourhood fabric, creating the fine-grained mixed-use visible along streets like Bur Oak Avenue. These smaller-scale interventions have generally maintained better occupancy and serve genuine neighbourhood needs.

The Mews: Suburban "5-Over-1" Approach

In contrast, The Mews—a purpose-built apartment building with ground-floor retail located on Cornell Park Avenue—represented a more conventional suburban approach to mixed-use. This "5-over-1" style development (residential over commercial) struggled with the same challenges facing many similar developments: insufficient foot traffic to support retail and competition from big-box stores.

The Mews on Cornell Park Avenue - a more conventional mixed-use building that struggled to maintain viable retail [Source: Victoria Moore]

Why the Difference?

The neighbourhood-integrated approach succeeded because it:

- Matched Scale to Market: Small commercial spaces suited to local entrepreneurs and services

- Served Local Needs: Corner stores and services that residents could genuinely walk to

- Lower Overhead: Smaller spaces with lower rents for local businesses

- Incremental Development: Could adapt organically to market conditions

Meanwhile, The Mews faced challenges common to larger mixed-use developments:

- Higher Rent Expectations: Larger spaces requiring higher revenue to be viable

- Competition from Big-Box: Nearby strip malls and big-box stores offered more convenience

- Insufficient Density: Not enough residents within walking distance to support specialty retail

- Car-Oriented Context: Residents still drove for most shopping needs

The Property Tax Subsidy Problem

A deeper issue highlighted by Strong Towns analysis is that big-box stores often receive an effective subsidy through lower property taxes per acre. While Cornell's mixed-use buildings generated high property tax revenue per acre due to their compact, multi-story design, competing big-box stores typically sit on large parcels with vast parking lots, resulting in much lower tax revenue per acre despite their success.

This creates an unfair competitive advantage for car-oriented development over walkable, mixed-use buildings. As our value-per-acre analysis of Langley demonstrates, the most financially productive areas are typically the walkable, mixed-use districts, not the sprawling commercial centers. However, current tax structures often fail to reflect this reality, inadvertently subsidizing the very development patterns that undermine walkable communities like Cornell's town center.

Zoning Innovation

Cornell's flexible zoning was revolutionary for Markham:

- Mixed residential and commercial in same blocks

- Live-work units throughout neighbourhoods

- Corner commercial in residential areas

- Reduced parking requirements for walkable locations

- Form-based rather than use-based regulations

Current Status

Neighbourhood Mixed-Use: Generally successful with corner stores, cafes, and services maintaining steady business

The Mews: Struggled with retail vacancies, now primarily service businesses (medical offices, real estate, etc.)

Future Plans

Recent planning efforts aim to strengthen mixed-use through:

- Higher density residential development

- Large-format grocery store

- Transit terminal near Highway 7

- High school to increase foot traffic

- More flexible restaurant zoning

Parks & Open Space Integration

Comprehensive Parks System

Cornell integrated an extensive network of parks and open spaces, following New Urbanist principles of providing green amenities within walking distance of all residents.

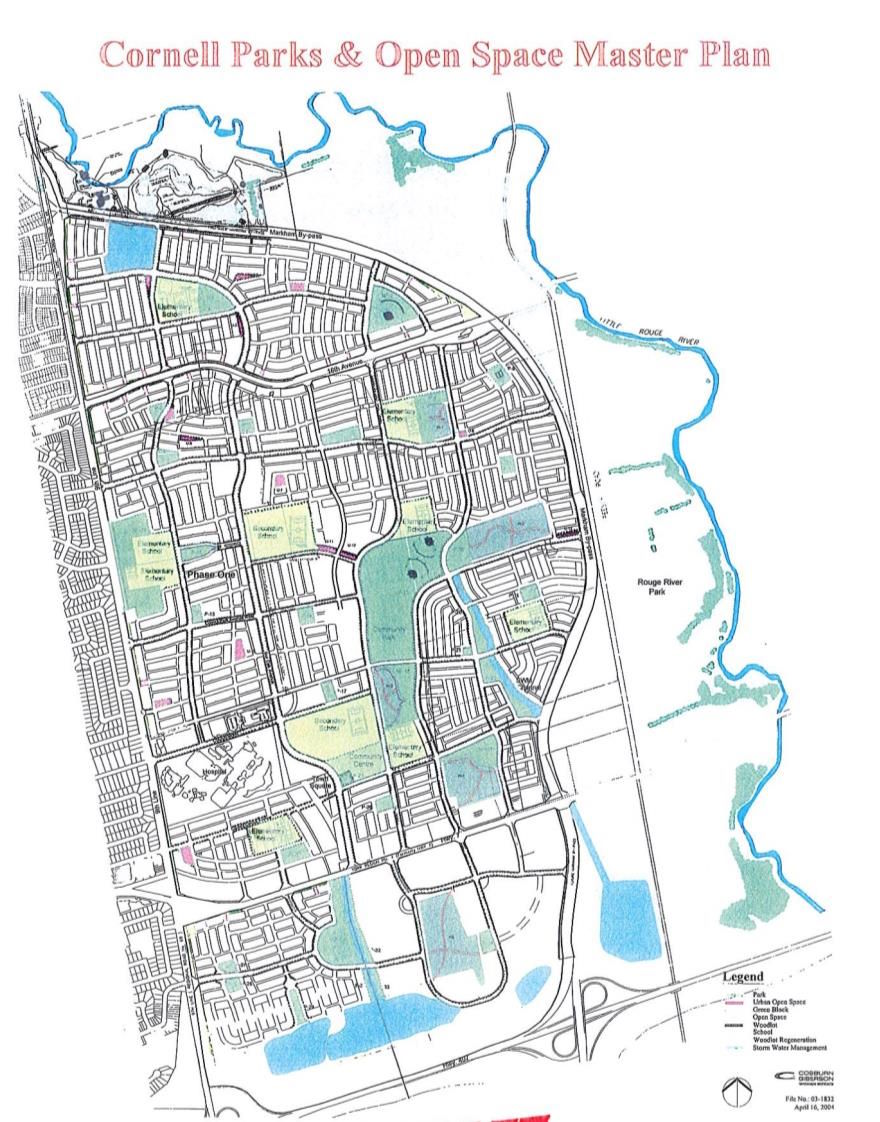

Cornell Parks and Open Space Master Plan showing interconnected green spaces [Source: Victoria Moore]

Park Hierarchy

- Neighbourhood Parks: Small parks serving local areas

- Community Parks: Larger facilities like Grand Cornell Park

- Green Corridors: Linear parks connecting neighbourhoods

- Natural Areas: Preserved existing woodlots and streams

- Recreational Facilities: Community center, library, and sports fields

Grand Cornell Park [Source: @baqirali / YouTube]

Design Challenges

While Cornell successfully integrated numerous parks, some design decisions highlight the tension between suburban and urban approaches:

- Road Barriers: Grand Cornell Park is surrounded on one side by a four-lane road, limiting walkable access

- Car-Oriented Access: Many residents still drive to parks despite living nearby

- Maintenance Costs: Extensive park system requires significant ongoing maintenance, though this can be offset by savings in stormwater infrastructure costs when parks provide natural drainage functions

Environmental Benefits

Cornell's park system provides important environmental functions:

- Stormwater management through infiltration

- Urban heat island mitigation

- Habitat preservation and restoration

- Air quality improvement

- Community gathering spaces

Lessons for Langley: Applying Cornell's Experience

Cornell's experience offers several positive lessons that could be applied in Langley:

Housing Diversity & Flexible Zoning

- Mixed Housing Types: Allow multiple housing types within the same block, as Cornell demonstrated successfully

- Less Prescriptive Zoning: Enable diverse housing forms to evolve organically rather than rigidly defining what can be built where

- Coach Houses: Permit laneway housing as gentle density

- Life-Cycle Housing: Provide options for residents at different life stages

Mixed-Use Integration

- Neighbourhood-Scale Mixed-Use: Encourage Cornell's successful model of small-scale commercial integrated into residential areas

- Basement Commercial: Learn from Cornell's mixed-use success and East Clayton's basement retail model to allow ground-floor and basement commercial in residential neighborhoods

- Live-Work Units: Enable businesses to operate from home while maintaining residential character

- Form-Based Approach: Focus on building form and relationship to the street rather than strict use categories

Street Design Innovation

- Laneway Model: Separate vehicular access from pedestrian streets

- Grid Connectivity: Create connected street networks with multiple routes

- Complete Streets: Design for pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles

- Traffic Calming: Use design to reduce vehicle speeds naturally

Community Building

- Public Participation: Use charrette processes to build consensus

- Walkable Scale: Design neighbourhoods around the five-minute walk

- Front Porches: Encourage social interaction through design

- Public Spaces: Integrate parks and gathering places throughout

Key Takeaway

Cornell demonstrates that New Urbanist principles can work in Canadian suburban contexts, particularly for residential development and street design. However, success requires careful attention to transit connectivity, sufficient density, and ongoing municipal support. The community's evolution over 25+ years shows both the promise and the need for adaptive management in creating walkable, diverse neighbourhoods.

References & Further Reading

- Moore, Victoria (2017): Exploring the New Urbanist Legacy in Cornell, Markham. Master's Research Paper, York University Faculty of Environmental Studies. Original Source

- Gordon, David L. A. & Tamminga, Ken (2002): Large-scale Traditional Neighbourhood Development and Pre-emptive Ecosystem Planning: The Markham Experience, 1989-2001. Journal of Urban Design, 7:3, 321-340

- Wikipedia: Cornell, Markham. Community overview and development history

- Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company: Official Website. The firm that designed Cornell's master plan

- City of Markham: Official Website. Current planning documents and community information

About Our Case Studies

These case studies were researched and compiled by Strong Towns Langley Chair, James Hansen, to identify successful implementations of people-first urban design principles that could inform development in our region.

Have a suggestion for a case study we should explore? Know of an interesting example of sustainable, financially resilient urban development?

Contact James directly at james@strongtownslangley.org, find him on our discord, or contact us with your ideas.

James Hansen

Strong Towns Langley Chair