Patrick Condon: The Story of East Clayton, a Modern Streetcar Suburb in Surrey, BC

East Clayton Neighbourhood Community Plan (2000)

Compiled from Headwaters Project Website.

The Headwaters Project Vision

East Clayton began as the visionary "Headwaters Project," led by Professor Patrick Condon through the UBC James Taylor Chair in Landscape and Liveable Environments. The project name referenced both the headwaters of streams in the area and the "headwaters" of new ideas for sustainable community design.

East Clayton's coach houses above garages provide rental housing while increasing density

Seven Sustainability Design Principles:

- Conserve land and natural systems by designing compact communities

- Lighten the "footprint" of streets and parking to reduce imperviousness

- Build different housing types to accommodate diverse age groups and income levels

- Create a fine-grained street network that can accommodate transit and connect local destinations

- Put services, jobs, and shopping within a five-minute walk of most homes

- Improve ecological health through stormwater infiltration and biodiversity

- Incorporate natural drainage systems to manage stormwater at the source

These principles were revolutionary for their time, integrating environmental sustainability with New Urbanist design in ways that influenced municipal planning across North America.

Revolutionary Housing Innovation

East Clayton's most significant contribution to Canadian planning was demonstrating how policy innovation could create affordable housing through creative zoning rather than subsidies. Patrick Condon called it "Canada's most successful experiment in affordable housing."

Housing Innovations:

1. Legal Secondary Suites

Most single-family homes were designed with legal basement suites, effectively doubling housing capacity while providing mortgage helpers for homeowners. This innovation was groundbreaking for Canadian suburbs.

2. Coach Houses

Small, detached dwelling units built above garages provided additional rental housing opportunities and increased density without changing neighbourhood character.

3. Live-Work Units

East Clayton pioneered live-work units with ground-floor or basement commercial spaces, allowing residents to operate businesses from home while maintaining residential character.

Basement-level retail space showing how commercial uses integrate into residential areas

Market Impact

The affordability strategy was remarkably successful initially, with virtually every home sold to buyers who couldn't have afforded similar housing without rental income. However, success created unintended consequences as market forces pushed toward using both basement suites and coach houses simultaneously.

Contemporary Context: Cornell vs East Clayton

East Clayton and Cornell in Markham, Ontario represent two different approaches to New Urbanist development during the same period. East Clayton focused on sustainable infrastructure and policy innovation, while Cornell, designed by Duany Plater-Zyberk and Associates, implemented traditional neighbourhood design principles. Both projects applied New Urbanist principles within Canadian regulatory and geographic contexts, offering complementary lessons for sustainable community development.

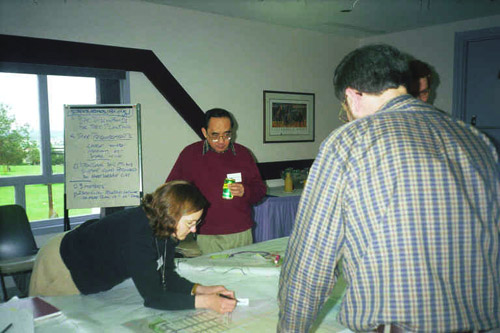

The Design Charrette: Breaking from the Engineering Textbook

East Clayton's innovative design emerged from a groundbreaking collaborative process that challenged conventional planning methods. Rather than following the typical "engineering textbook" approach to subdivision design, the project used intensive design charrettes to bring together diverse stakeholders in creative problem-solving sessions.

The Charrette Process (April-May 1999)

The East Clayton Neighbourhood Concept Plan was developed through a four day intensive design charrette:

- Design Brief Preparation: April 14-15 (Part I) and May 4-5 (Part II)

- Charrette: May 6-11, 1999 (excluding weekends - May 6, 7, 10, 11)

Diverse Stakeholder Participation

The charrette brought together representatives from multiple constituencies, each contributing essential expertise:

- Environment: Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Environment Canada, BC Environment

- Utilities & Services: BC Tel, TransLink, BC Hydro, Canada Post, Rogers Cable

- Community: Clayton Area Citizens Committee, East Clayton Property Owners Society

- Education: School District representatives

- Development: Industry professionals and landowners

- Municipal: Surrey engineering, planning, and operations staff

Creative Design vs. Standard Engineering

The charrette process specifically sought to move beyond conventional engineering standards that prioritized cars over community. By bringing stakeholders together in intense collaborative sessions, the process:

- Encouraged creative problem-solving over adherence to standard practices

- Built consensus among groups that typically worked in isolation

- Integrated environmental, social, and economic considerations from the outset

- Produced innovative solutions that no single profession could have developed alone

Charrette: Participants collaborating on neighbourhood design, May 1999 (Source: Headwaters Project)

Charrette: Patrick Condon visible in the right-centre of the frame, surrounded by other participants, May 1999 (Source: Headwaters Project)

Charrette: The recognizable road layout of East Clayton is visible, May 1999 (Source: Headwaters Project)

Charrette Success Factors

- Intensive Collaboration: Concentrated time periods forced creative breakthrough

- Diverse Expertise: Multiple professional perspectives at one table

- Community Input: Residents and property owners as equal participants

- Municipal Buy-in: City staff as active collaborators, not just reviewers

- Visual Communication: Ideas expressed through drawings and models

Green Infrastructure Challenges

While East Clayton successfully implemented many innovative design features, one of its most ambitious environmental goals—natural stormwater management—illustrates the challenge of implementing green infrastructure.

Vision vs. Reality

The East Clayton NCP outlined natural drainage systems including roadside swales, infiltration wells, and preserved drainage channels. However, these systems were never implemented. Instead, developers and the city opted for a conventional 100-year storm sewer system at significantly higher cost.

Why Green Infrastructure Failed

- Developer Concerns: Disliked the "unfinished" appearance of grassy swales

- Municipal Risk Aversion: Worried about maintenance and long-term performance

- Market Preferences: Buyers preferred conventional concrete curbs and manicured streetscapes

- Regulatory Barriers: Existing standards favored proven conventional systems

This outcome exemplifies the expensive infrastructure burden that Strong Towns advocates highlight—missed opportunities for environmental benefits and cost savings, replaced with infrastructure debt that future residents will bear.

Green Infrastructure Renaissance

Two decades later, we are seeing a stronger push for green infrastructure than ever before. Climate change, urban flooding, and mounting infrastructure costs have made natural systems more attractive to municipalities and developers alike. Recently, Strong Towns Langley hosted an event with Professor Sean Markey from Simon Fraser University, who outlined innovative approaches to integrating nature into urban design in his new book "Nature-First Cities." Professor Markey's research demonstrates how urban greenspace and green infrastructure can complement traditional infrastructure while providing ecological, economic, and social benefits that contribute to the health and well-being of urban dwellers.

East Clayton Live-Work Success: Creative Neighbourhood Commerce

East Clayton in Google Maps 3D View | Go To Street View

While many New Urbanist developments struggle with mixed-use commercial, East Clayton has quietly achieved something remarkable: genuine neighbourhood businesses integrated into residential areas. The live-work concept has evolved into creative solutions that serve local needs while maintaining residential character.

Successful Neighbourhood Commerce

East Clayton's commercial areas demonstrate how flexible zoning can enable innovative business models:

- Basement Daycare: A successful childcare business operates from a basement space along the 68th Avenue strip, serving local families while exemplifying the live-work concept

- Home-Based Services: Professional services, consultants, and creative businesses operating from residential live-work units

- Neighbourhood-Scale Retail: Small shops and services that genuinely serve walking customers from the immediate area

- Flexible Commercial Spaces: Ground-floor and basement commercial areas that can adapt to changing business needs

Innovation in Practice

The live-work areas along 68th Avenue between 188th and 192nd Streets showcase how mixed-use development can work at a neighbourhood scale:

- Businesses that serve local residents' daily needs

- Entrepreneurs who live and work in the same community

- Flexible spaces that can accommodate different business types over time

- Integration of commercial uses without disrupting residential character

Beyond the Strip Malls

While East Clayton does include conventional strip mall development along Fraser Highway, the real innovation lies in the fine-grained commercial integration throughout residential areas. This model provides:

- Convenient services within walking distance

- Opportunities for local entrepreneurship

- Community gathering places at neighbourhood scale

- Economic diversity supporting local residents

Basement-level commercial space showing how businesses integrate into residential areas

Live-Work Success Factors

- Flexible Zoning: Regulations that enable rather than restrict business innovation

- Residential Integration: Commercial uses that complement rather than disrupt neighbourhood life

- Local Market Focus: Businesses serving immediate community needs

- Adaptive Spaces: Commercial areas that can evolve with changing business models

- Community Support: Residents who value and patronize local businesses

Policy Innovation Success

East Clayton's live-work model has influenced zoning changes across BC, demonstrating how pilot projects can drive broader policy innovation. The basement daycare and other neighbourhood businesses prove the concept works in practice.

Long-Term Outcomes & Current Evolution

Successes After 20+ Years

- Housing Diversity Model: Secondary suites and coach houses successfully integrated into numerous BC communities

- Environmental Innovation: Stormwater management techniques adopted widely across Lower Mainland

- Policy Influence: Planning innovations studied by municipalities across North America

- Density Achievement: Higher density than typical suburbs while maintaining neighbourhood character

- Community Building: Strong neighbourhood identity and resident engagement

- Academic Legacy: Continues to be studied as model for sustainable development

Learning and Adaptation

East Clayton's evolution demonstrates the importance of learning from experience:

- Parking Solutions: Community and municipal efforts to address parking challenges through better management and enforcement

- School Planning: Enhanced coordination between housing development and educational capacity planning

- Infrastructure Adaptation: Modifications to environmental systems based on real-world performance

- Commercial Evolution: Growing success of neighbourhood-scale businesses serving local needs

Current Planning Evolution

East Clayton continues evolving through new planning initiatives:

Clayton Corridor Plan (2024)

Surrey's latest planning effort addresses transit-oriented development around future SkyTrain stations:

- Two Transit-Oriented Areas covering 277 acres

- Integration with Surrey-Langley SkyTrain extension

- Stations planned at 184th Street and 190th Street

- Higher density development around transit nodes

Community Amenities

Recent investments in community infrastructure:

- Clayton Community Centre (2023): North America's first Passive House certified community centre

- School Expansion: Ongoing efforts to address capacity challenges

- Park Improvements: Enhanced recreational facilities and programming

Key Insight

East Clayton demonstrates that successful sustainable development requires ongoing adaptation and management, not just initial visionary planning. The community's evolution provides valuable lessons for long-term stewardship of innovative development.

West Clayton: A More Conventional Approach

Approved in 2015, West Clayton represents Surrey's a more typical approach to development. While it expands on East Clayton's built form, it adopts a more conventional implementation strategy.

What West Clayton Preserved

- Mixed Housing Types: Maintains diversity of housing forms and densities

- Live-Work Options: Continues mixed-use concepts but with more restrictive locations

- Walkable Design: Grid street network and transit-oriented development

- Energy Innovation: First "Energy Shift Neighbourhood" with density bonuses tied to energy efficiency

What Changed from East Clayton

- Planning Process: Conventional public consultation rather than intensive design charrettes

- Regulatory Flexibility: Comprehensive Development zoning required for innovations, creating bureaucratic barriers

- Housing Innovation: Optional rather than mandatory coach houses and live-work features

- Fire Separation: No requirement for pre-built commercial-residential separation, limiting future adaptability

- Arterial Roads: Conventional 4-lane arterial infrastructure rather than minimal 2-lane arterials designed to calm traffic

From a financial sustainability standpoint, East Clayton's approach to arterial roads was remarkably prescient. By planning mostly 2-lane arterials and forcing traffic to disperse through the local grid network, East Clayton minimized the massive infrastructure liability that wide arterials represent while creating human-scaled streets that could support productive, walkable development. West Clayton's reversion to conventional 4-lane arterials with medians and turn bays represents a return to the expensive, maintenance-intensive infrastructure that burdens municipalities with long-term financial obligations while generating relatively little tax revenue per mile. East Clayton understood that streets should prioritize wealth-building local commerce over high-speed traffic movement, while West Clayton chose the conventional engineering approach that prioritizes car throughput over community financial resilience.

Additionally, West Clayton's less prescriptive approach may actually reduce long-term flexibility for individual homeowners. Without mandatory fire separation between residential and potential commercial spaces, homeowners cannot easily convert basements or ground floors to businesses later. The optional nature of coach houses means fewer properties are built with the infrastructure to support additional rental units. Where East Clayton's "rigid" requirements created buildings ready for multiple uses, West Clayton's "flexible" zoning often locks buildings into single uses unless owners can navigate expensive rezoning processes.

While it's positive that West Clayton continues elements of East Clayton's design language, it is a less progressive and more suburban plan. It illustrates how bold innovation can be diluted through conventional planning processes, and how without institutional change, neighbourhood design can be pulled back to conventional suburban-style planning approaches.

Relevance to Langley: A Local Success Story

As a neighboring municipality with similar development patterns and challenges, East Clayton offers numerous lessons for Langley's future growth:

Direct Policy Applications

- Secondary Suite Integration: East Clayton's basement suite model provides proven approach for increasing housing options

- Coach House Development: Laneway housing demonstrates gentle density that maintains neighbourhood character

- Live-Work Flexibility: Zoning approaches that enable small businesses in residential areas

- Environmental Infrastructure: Stormwater management techniques adapted to Lower Mainland conditions

- Collaborative Planning: Community engagement processes that build consensus around innovation

Implementation Lessons

- Parking Planning: Learn from East Clayton's challenges to provide adequate parking for density

- School Coordination: Plan educational capacity concurrent with housing development

- Transit Integration: Coordinate development timing with transit infrastructure

- Commercial Realism: Understand market limitations for walkable retail in suburban contexts

- Long-term Stewardship: Plan for ongoing community management and infrastructure maintenance

Most importantly, East Clayton demonstrates that innovative, sustainable development can succeed commercially in Lower Mainland markets while providing genuine benefits for affordability, environmental performance, and community building. By studying both East Clayton's successes and challenges, Langley can adopt effective elements while avoiding implementation pitfalls.

References & Further Reading

- University of British Columbia James Taylor Chair: Headwaters Project Website - Original project documentation and research

- Nathan Pachal: East Clayton and Commercial Development (2013) - Analysis of mixed-use implementation challenges

- City of Surrey: East Clayton Neighbourhood - Official city information and current planning

- City of Surrey: Clayton Corridor Plan (2024) - Future transit-oriented development planning

- Patrick Condon: "Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities" - Book examining East Clayton and other sustainable development examples

- Patrick Condon: "Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities" (2007) - Comprehensive guide to the collaborative planning methodology developed through East Clayton

- Surrey Now-Leader: Read about East Clayton's history from the prof who helped design it - Patrick Condon's perspective on the project

- Canadian Architect: Clayton Community Centre: Passive House Achievement - Recent sustainable infrastructure developments

About Our Case Studies

These case studies were researched and compiled by Strong Towns Langley Chair, James Hansen, to identify successful implementations of people-first urban design principles that could inform development in our region.

Have a suggestion for a case study we should explore? Know of an interesting example of sustainable, financially resilient urban development?

Contact James directly at james@strongtownslangley.org, find him on our discord, or contact us with your ideas.

James Hansen

Strong Towns Langley Chair